For Americans, the politics of the Middle Ages tends to concern one form of government: monarchy. But Canada, composed of the British colonies of North America which did not reject monarchy in the late eighteenth century, seems to have historically held a strikingly different view of how the Middle Ages fall in the narrative of political progress. In the British tradition of constitutional monarchy, after all, the origins of the parliamentary system lie in the Magna Carta of 1215. Over the following centuries, this early-established constitutional monarchy gradually evolved into the recognizably republican system that Canada was subject to by the mid-19th century.

Construction of Parliament Hill’s Centre Block in 1863.

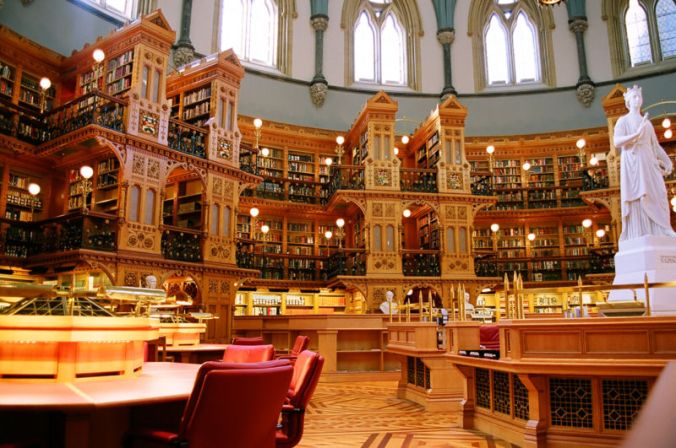

Parliament Hill (the collective name for the Canada’s capitol buildings in Ottawa), built between 1859 and 1876, was designed as the visual antithesis to the United States Capitol building. Rejecting the Capitol’s neoclassical architectural precedent for seats of legislative government, Parliament Hill was constructed in a decidedly Gothic Revival style, following the lead of the UK’s still-under-construction Palace of Westminster. The bold architecture of Parliament Hill gave the medieval parliamentary tradition a seat of administration for North America. The buildings of Parliament Hill are even situated on a dramatic mount that rises high above the Ottawa River, as if a European castle. Among the most prominent structures in this complex is the Library of Parliament, in the form of a fantastical Gothic rotunda. This building presents medievalism as not just compatible with, but consistent with intellectualism. The architecture of Parliament Hill places Canada’s seat of republican government within a vestibule of medievalist sensibility.

The fanciful Gothic interior of the Library of Parliament.

The use of medieval imagery in the buildings of Parliament Hill expresses just how maneuverable referencing the Middle Ages can be in modern political discourse (even visually). In the United States, the medieval is frequently viewed as politically reactionary. In Canada, the medieval can connote a tradition of political reform that finds its origins in 13th century England. In both, the medieval has a history of snaking its way into contemporary political rhetoric.

Looking at Canada as an example of medieval inspired architecture made me wonder if any other countries that were once British colonies and did not reject monarchy until fairly recently from a historical standpoint also exhibited similar types of inspired architecture. I think India would be a good country to examine for this as it was under British control during the late middle ages and did not fully reject living under British rule until around 70 years ago. Also it is worth noting that even though the United States did reject monarchy and British rule fairly early compared to other former colonies, there are still many evidences of medieval architecture all across the U.S. Flying buttresses would be a common example.

LikeLike

This is a good point. I think medievalist architecture has been used over the years for a lot of different ends. Parliament Hill’s architecture may have been used to celebrate an English-derived system of government, but medievalist architecture elsewhere, including in the U.S., has been used for everything from embracing ethnic heritage to inventing altogether new architectural styles (check out H.H. Richardson’s work). And a number (but probably not all) of these uses may have political connotations as well.

LikeLike

In addition, I think it’s interesting that the neoclassical architecture that the U.S. embraced early on to harken back to the Roman Republic was contemporaneously used in Napoleon’s French Empire to harken back to the Roman Empire. And even medieval Romanesque architecture was revived in the U.S. in the 19th century for being more down-to-earth than the lofty Greek Revival architecture that was popular at the time. Architectural revivals can be used for contradictory political ends.

LikeLike

There are many modern places in the world that use a medieval design for architecture. I do think you bring up an interesting reason behind Canada using this style because they accepted the monarchy. I believe the main reason behind this architecture still being used today would because it makes people believe a building is older than it actually is.

LikeLike

This blog post, as well as our discussion on Monday, raised questions for me as to whether some of the modern American perception of medieval times as barbaric and uncivilized are due to the American aversion towards monarchy as the antithesis of democracy and freedom. The prevalence of monarchies in the Middle ages could explain why they are viewed as distinctly uncivilized compared to civilizations of antiquity such as Athens, the “birthplace of democracy”, or the Age of Enlightenment as the spiritual and philosophical precursor to American democracy. In no way does this account for all misconceptions that Americans hold towards the Middle Ages, but I would argue it has an impact on the attitude of the average American towards medieval times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! And I think it is interesting that these generalizations that our culture makes about entire historical eras are not even exactly true. Much of classical Greece outside of Athens had monarchies in Antiquity, and in the eighteenth century, absolutist monarchs took advantage of the rationalism of the Enlightenment to consolidate their power.

LikeLike

Yeah, in thinking about this it is hard to decide whether we are wrongly diagnosing a cause of medieval misconceptions, as the medieval period is certainly not alone in containing non-democratic governments, or whether it is a cause that is due to historical misconceptions in general and the strong association most people have of the Middle Ages and monarchy.

LikeLike

Is it actually that the American aversion is only towards monarchy or just all forms of government that aren’t a free market republic? It seems as though throughout history ever since the United States was formed we have looked down on the way that other countries are run. So if we say that we celebrate Greek culture because they had a similar government to us and that we misconceive what we think of the Middle Ages because we don’t like monarchies, could we expand that thought onto other forms of government such as Communism for example? I wonder if we would find similar inaccuracies when comparing misconceptions about the USSR and the Middle Ages.

LikeLike

You bring up a good point in referencing the fact that we have a much higher aversion to using Greek architecture and this could be attributed to the fact that we align ourselves more with them. Yet I don’t really understand the question that you are asking. To me it seems to you are trying to reference more than just architecture and why we have certain aversion to one over the other. Instead it seems as if you are trying to reference a deeper point in to why do we have an aversion to certain ideals and forms of governmental control. I also believe that our misconceptions about the Middle Ages do not come from our dislike of monarchies but instead from the fact that many of our sources from the Middle Ages give use the misconceptions or never truly give use the full picture.

LikeLike

Architecture is a means of expression. As discussed, architectural features can be associated with political ideology. For example, architectural programs associated with the medieval and monarchy incorporate the use of, the ribbed vault, flying buttress, and pointed arch. Classically-inspired architecture that we associate with democracy include features such as, columns, domes, and a strict adherence to

proportions. The irony inherent in both of these architectural styles, though, is that they do not find their origins in governmental buildings. They are offshoots of religious architecture such as the gothic cathedral of St. Denis in France (1144) and the classic Parthenon temple in Athens (447 BCE). The connection between religion and politics may add another dimension to how we look at architecture.

LikeLike

The United States obviously rejects medievalism in most forms, and I agree with you to an extent that it has to do with the rejection of monarchism in America. However, I do also wonder if it has to do with the separation of church and state. The United States made the separation of church and state one of the key components of itself. Meanwhile, Canada does not have express separation of the two in their constitution. The were obviously a large overlap between religion and the state during the middle ages, and I can’t help but wonder if that has to do with the rejection of the middle ages in the United States.

LikeLike